Opioid Hyperalgesia Diagnostic Tool

This tool helps clinicians identify key clinical signs that may indicate opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH) rather than tolerance. Based on evidence from the article, OIH is characterized by worsening pain with increasing opioid doses, spreading pain areas, and changes in pain quality.

Clinical Assessment

Answer the following questions based on your patient's presentation:

When More Opioids Make Pain Worse

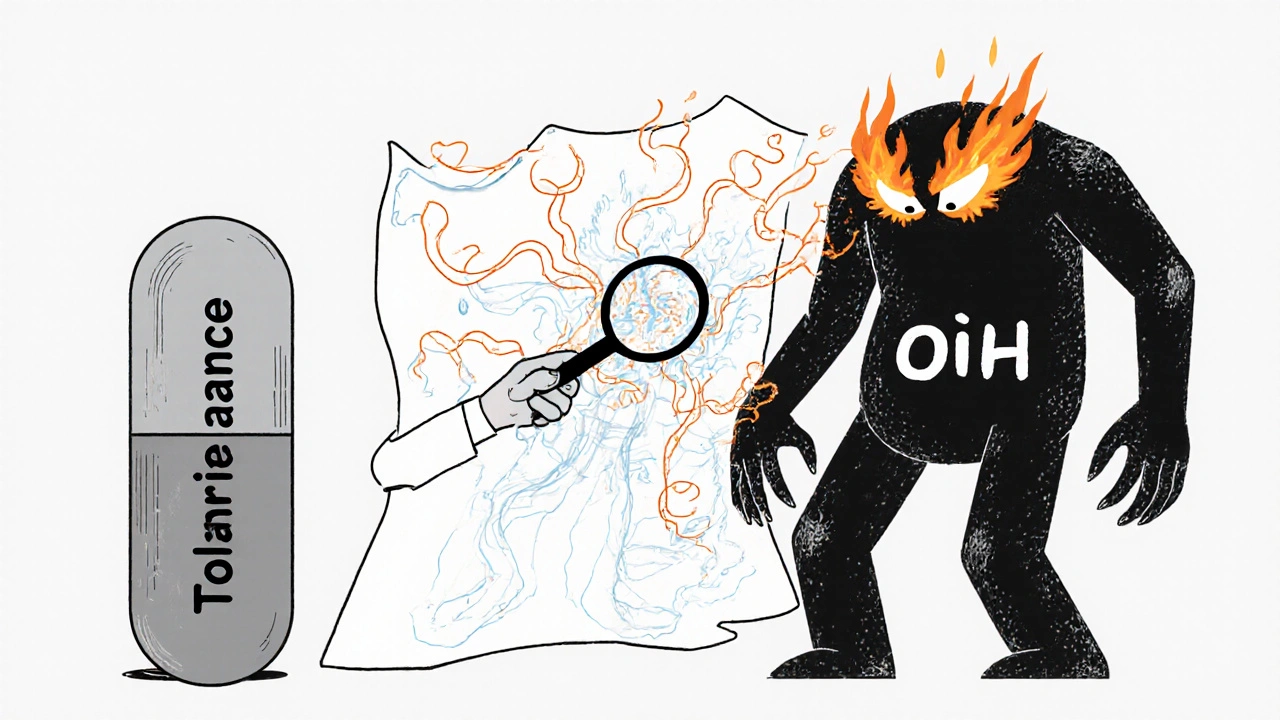

Imagine taking higher doses of opioids because your pain isn’t controlled-only to find it gets worse. This isn’t a rare fluke. It’s opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH), a real and often misdiagnosed condition where the very drugs meant to ease pain actually make you more sensitive to it. Unlike tolerance, where your body just needs more drug to get the same effect, OIH flips the script: more opioid = more pain. And too many clinicians mistake it for worsening disease or poor adherence, leading to dangerous dose escalations that trap patients in a cycle of increasing discomfort.

What Is Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia?

Opioid-induced hyperalgesia isn’t just a theory. It’s been shown in lab studies and observed in patients on long-term opioid therapy. The body responds to prolonged opioid exposure by turning up the volume on pain signals-literally. Neurobiological changes like NMDA receptor activation, spinal dynorphin release, and glial cell inflammation amplify pain processing. Patients may start feeling pain in areas that were never affected before. Light touch might hurt (allodynia). A dull ache could turn sharp or burning. Pain spreads beyond the original injury site-something that doesn’t happen with simple tolerance.

Think of it this way: tolerance means the drug stops working as well. OIH means the drug starts actively making your nervous system more sensitive to pain. It’s not about needing more for relief-it’s about the treatment itself becoming part of the problem.

How Is It Different from Tolerance?

Tolerance and OIH often look similar on the surface: both involve rising opioid doses and persistent pain. But their underlying mechanisms and clinical responses are opposites.

| Feature | Opioid Tolerance | Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia |

|---|---|---|

| Pain response to higher doses | Pain improves or stabilizes | Pain gets worse |

| Pain distribution | Stays in original location | Spreads to new areas |

| Pain quality | Same as original pain | Changes-new sensations like burning, tingling, allodynia |

| Response to dose reduction | Pain may return or worsen temporarily | Pain often improves |

| Underlying mechanism | Receptor downregulation | NMDA activation, glial inflammation |

Here’s a real-world example: A patient with lower back pain starts on oxycodone. After six months, their pain spreads to their hips and thighs. Even light clothing causes discomfort. They’ve doubled their dose, but the pain keeps climbing. That’s not tolerance-that’s OIH. If you keep increasing the opioid, you’re feeding the fire.

Red Flags That Suggest OIH, Not Tolerance

Not every patient on high-dose opioids has OIH. But if you see these patterns, suspect it:

- Pain worsens despite increasing opioid doses

- New pain areas appear-especially beyond the original injury zone

- Non-painful stimuli (like a breeze or a bedsheet) now cause pain (allodynia)

- Pain quality changes: dull → sharp, constant → shooting, localized → widespread

- Pain persists or worsens during stable dosing (not just during withdrawal)

- No clear structural or disease progression to explain the worsening pain

One of the biggest clues? Pain improves when you reduce the opioid dose-or switch to a different one. That’s the opposite of what you’d expect with tolerance. If lowering the dose helps, you’re likely dealing with OIH.

Why It’s So Often Missed

OIH is tricky because it mimics so many other things: disease progression, nerve damage, depression, or even addiction. Many clinicians assume increased pain means the original condition is getting worse-so they prescribe more opioids. But research shows this pattern is common in patients on chronic therapy, especially those on doses above 100 mg morphine equivalents per day.

Studies like the Stanford trial NCT00246532 tried to map how OIH develops across different pain types and populations. They found it doesn’t always show up the same way. Some patients develop mechanical allodynia. Others show thermal hypersensitivity. The variation makes diagnosis harder-but not impossible.

Also, there’s still debate over how often OIH occurs in real-world settings. Some systematic reviews call the evidence "stimulus-dependent," meaning it shows up more clearly in lab tests than in routine clinic visits. But that doesn’t mean it’s rare-it means we’re not measuring it right.

How to Diagnose It in Practice

You don’t need fancy equipment to suspect OIH. Here’s what works:

- Track pain maps: Have patients draw where their pain is at every visit. Look for spreading patterns.

- Record dose-pain relationships: Note if pain gets worse after each dose increase. Plot it like a graph.

- Ask about new sensations: "Has anything started hurting that didn’t before? Like light touch, cold, or pressure?"

- Try a cautious taper: If pain improves by 20-30% after reducing the opioid by 20-25% over 1-2 weeks, OIH is likely.

- Use standardized tools: Tools like the PainDETECT questionnaire or quantitative sensory testing (QST) can help, but aren’t always needed.

Don’t wait for perfect data. If the clinical picture fits, treat it as OIH until proven otherwise. The risk of doing nothing is far greater than the risk of reducing opioids too quickly.

What to Do When You Suspect OIH

Stop escalating. That’s the first rule.

For OIH, the goal isn’t to fight pain with more opioids-it’s to reset the nervous system. Options include:

- Gradual opioid reduction: Slowly lower the dose over weeks. Don’t stop cold turkey-this can trigger withdrawal and confuse the picture.

- Opioid rotation: Switch from morphine or oxycodone to methadone or buprenorphine. These have different receptor profiles and may reduce NMDA activation.

- Add NMDA antagonists: Low-dose ketamine (oral or nasal) or dextromethorphan can block the hyperalgesia pathway. Some clinics use them off-label with good results.

- Non-opioid alternatives: Gabapentin, duloxetine, or nortriptyline help with neuropathic pain components. Physical therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, and graded activity are critical.

One UK pain clinic reported that 60% of patients labeled as "tolerant" improved significantly after switching from oxycodone to buprenorphine and adding gabapentin. Their average daily opioid dose dropped by 45%, and pain scores fell by 30% in 12 weeks.

The Bigger Picture: Why This Matters

Opioid prescribing has dropped sharply since 2018-New Zealand’s dispensing rate fell from 1.07 to 0.89 daily doses per 1,000 people by 2021. That’s partly because of growing awareness of OIH and other harms. Regulatory agencies like Medsafe, the FDA, and EMA now explicitly warn against long-term opioid use for chronic non-cancer pain.

When OIH is misdiagnosed, patients end up on higher doses longer, increasing risks of dependence, respiratory depression, and overdose. Hospital stays get longer. Readmissions go up. And the patient’s quality of life plummets.

But there’s hope. As clinicians get better at spotting OIH, more patients can be weaned off opioids safely and transitioned to sustainable, non-addictive pain management strategies. This isn’t about denying pain relief-it’s about giving real relief.

Final Takeaway

If your patient’s pain is getting worse on higher opioid doses, don’t assume it’s tolerance. Ask: Is the pain spreading? Has the quality changed? Does it hurt more when I touch the skin? If yes-OIH is likely. Reduce the opioid. Switch the drug. Add non-opioid therapies. And stop chasing pain with more pills. Sometimes, the best way to stop pain is to give less of what’s making it worse.

Can opioid hyperalgesia happen with short-term use?

Opioid-induced hyperalgesia is primarily seen with long-term use-typically weeks to months of daily therapy. While rare cases have been reported after just a few days of high-dose IV opioids in ICU settings, it’s not common in short-term use like post-surgery. The risk rises significantly after 4-6 weeks of continuous use.

Is OIH the same as addiction?

No. Addiction involves compulsive use despite harm, cravings, and loss of control. OIH is a physiological change in pain processing. A patient can have OIH without being addicted, and vice versa. But they can coexist. Misdiagnosing OIH as addiction can lead to stigma and poor care.

Can I test for OIH with a blood test or scan?

No reliable blood test or imaging scan exists yet to diagnose OIH. Diagnosis relies on clinical signs: pain worsening with dose increases, spreading pain, allodynia, and improvement after dose reduction. Research into biomarkers (like genetic markers or inflammatory proteins) is ongoing, but not ready for clinical use.

What if reducing opioids makes the pain worse?

If pain spikes after reducing opioids, it could be withdrawal, not OIH. Withdrawal usually includes other symptoms like sweating, anxiety, nausea, and insomnia. OIH pain improves with dose reduction. If pain gets worse without other withdrawal signs, it might still be OIH-try slowing the taper. A slow, steady reduction over 4-8 weeks often helps the nervous system recalibrate.

Are there any opioids that don’t cause OIH?

All opioids can potentially cause OIH with long-term use, but some carry lower risk. Buprenorphine, a partial opioid agonist, appears to cause less NMDA activation and is less likely to trigger hyperalgesia. Methadone also has NMDA-blocking properties, which may offer some protection. Still, no opioid is completely risk-free for long-term use.

How common is OIH in chronic pain patients?

Exact rates are unclear, but studies suggest 10-30% of patients on long-term high-dose opioids may develop OIH. It’s underdiagnosed because many clinicians don’t look for it. The more opioids a patient takes and the longer they take them, the higher the risk.

Next Steps for Patients and Providers

If you’re on long-term opioids and your pain is worsening:

- Keep a daily pain diary: note location, intensity, quality, and dose timing.

- Ask your provider: "Could this be opioid-induced hyperalgesia?"

- Request a pain map review at your next visit.

- Explore non-opioid options like physical therapy, mindfulness, or nerve-targeted medications.

If you’re a provider:

- Don’t automatically increase opioids for rising pain.

- Use the clinical clues above before escalating.

- Refer to pain specialists when OIH is suspected.

- Stay updated on guidelines from Medsafe, NICE, and the CDC-opioid prescribing is evolving fast.

The goal isn’t to eliminate opioids entirely-it’s to use them wisely. When pain gets worse on more pills, it’s time to rethink the strategy. Sometimes, less is more.

vinod mali

November 17, 2025 AT 02:04Doctors need to stop thinking 'more is better' when pain gets worse.

Jennie Zhu

November 18, 2025 AT 07:38Kathy Grant

November 19, 2025 AT 12:00It’s not about quitting pain meds. It’s about stopping the war inside the body.

Robert Merril

November 20, 2025 AT 22:38Also methadone is way better for this btw. Just sayin

Noel Molina Mattinez

November 21, 2025 AT 04:51Roberta Colombin

November 22, 2025 AT 23:23Let’s stop treating people like numbers on a chart.

Dave Feland

November 24, 2025 AT 11:46Ashley Unknown

November 25, 2025 AT 22:34Georgia Green

November 27, 2025 AT 13:48Christina Abellar

November 28, 2025 AT 05:36Eva Vega

November 30, 2025 AT 01:12