Before 1995, a country like India could make life-saving HIV drugs for a fraction of the cost charged by big pharmaceutical companies. They didn’t invent the drugs, but they made them anyway-using different manufacturing processes to avoid violating patents. That changed overnight when the TRIPS agreement came into force. Suddenly, every WTO member had to grant 20-year product patents on medicines. No more shortcuts. No more low-cost generics. For millions in low-income countries, this wasn’t just a legal shift-it was a death sentence waiting to happen.

What the TRIPS Agreement Actually Does

The Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) Agreement is the global rulebook for how countries must protect patents, trademarks, and copyrights. It was written in 1994 during the Uruguay Round of trade talks and took effect on January 1, 1995. While it covers everything from music copyrights to software, its biggest impact has been on medicines. Under TRIPS, every country must now grant patents on pharmaceutical products, not just processes. Before TRIPS, only 23 of 102 developing countries allowed product patents for drugs. After? Nearly all of them. The standard? A minimum 20-year monopoly from the date the patent is filed. That means even if a drug was invented in 2005, no generic version can legally enter the market until 2025-even if the disease has killed millions in the meantime. TRIPS also forces countries to stop using old tricks. Before 1995, Indian manufacturers could reverse-engineer drugs using different chemical pathways. That’s no longer allowed. If a drug is patented, even if you make it differently, you’re breaking the law. And it’s not just about patents. TRIPS introduced data exclusivity-meaning regulators can’t approve a generic drug based on the original company’s clinical trial data for five to ten years after approval, even if the patent has expired. That’s a second barrier, hidden in plain sight.How TRIPS Blocks Generic Medicine Access

The idea behind TRIPS was simple: reward innovation. Big pharma argues that without strong patents, no one would spend billions developing new drugs. But the cost of that reward? Millions of people who can’t afford treatment. In 2001, a person in South Africa needed antiretroviral drugs for HIV. The branded version cost $10,000 per year. The generic version made in India? $350. That’s a 96% price drop. But under TRIPS, South Africa couldn’t import those generics without risking a lawsuit. Fourteen pharmaceutical companies sued the country in 1998 for trying to make affordable drugs available. The global outcry forced them to drop the case-but the message was clear: if you try to help your people, you’ll be punished. Even when countries try to use the legal escape hatches in TRIPS, they’re blocked. Article 31 lets governments issue compulsory licenses-allowing others to make a patented drug without the company’s permission. But there’s a catch: the license must be used “predominantly for the domestic market.” So if you’re a small country with no drug factories, like Rwanda, you can’t import generics from India even if they’re made under a legal license. That rule was designed to protect big pharma’s profits, not patients’ lives.The Doha Declaration and the Broken Promise

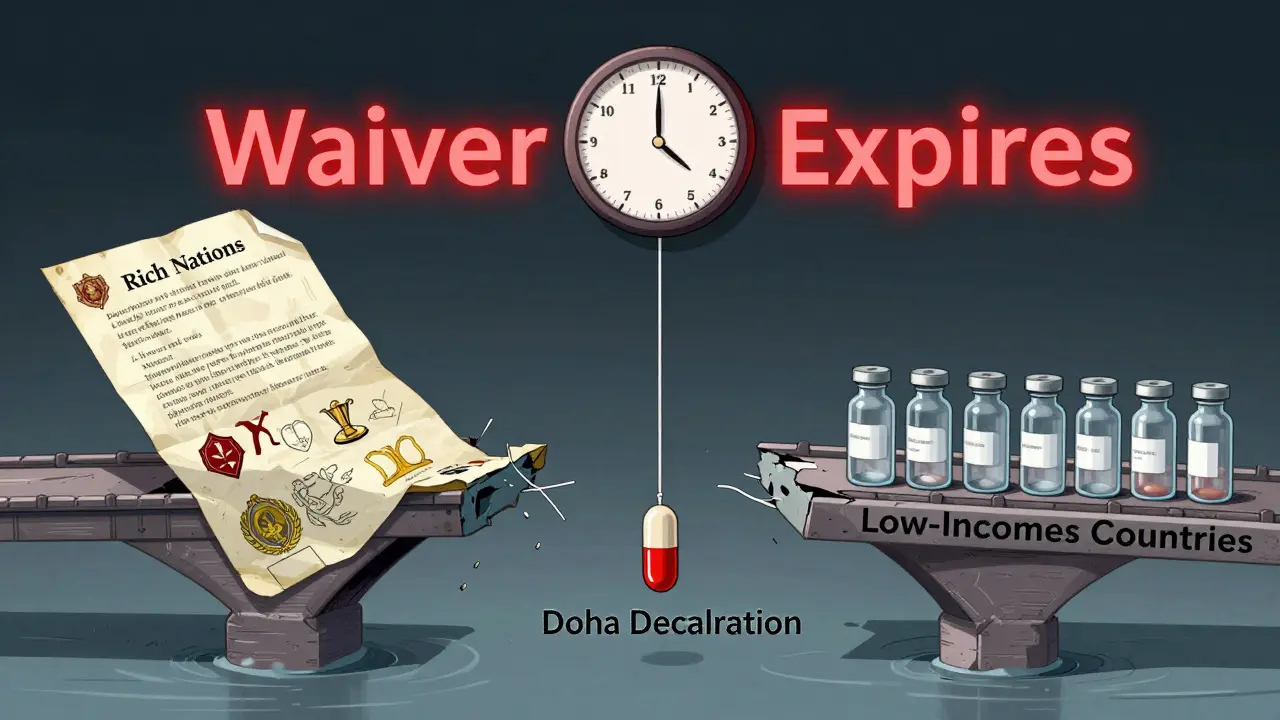

In 2001, after years of protests and deaths, the WTO finally admitted the problem. The Doha Declaration on TRIPS and Public Health said countries have the right to protect public health and can use compulsory licensing even in non-emergency situations. It was a win. But it didn’t fix the real issue: the “domestic market” rule. So in 2005, they added a workaround-the “Paragraph 6 Solution.” It allowed countries without manufacturing capacity to import generics made under compulsory license. Sounds good, right? In theory. In practice? It’s a bureaucratic nightmare. You need two licenses: one from the exporting country and one from the importing country. You need special labeling. You need to prove you’re not re-exporting. And you need to convince a pharmaceutical company to let you use their patent. By 2016, only one shipment of malaria medicine had ever been sent under this system. One. For a disease that kills over 600,000 people a year. Countries like Brazil and Thailand tried using compulsory licensing for HIV and cancer drugs. They got slapped with trade threats from the U.S. and EU. Brazil’s government was threatened with sanctions. Thailand’s health ministry was pressured to cancel licenses. The message? Don’t challenge the system. Even when you’re within the rules.

TRIPS Plus: The Hidden Rules That Make Things Worse

TRIPS is already strict. But rich countries didn’t stop there. Through bilateral trade deals, they pushed for “TRIPS Plus” rules-standards even tougher than the WTO requires. The U.S. and EU now demand extra patent extensions in free trade agreements. Some agreements add five extra years to patent life. Others ban generic manufacturers from even applying for approval until the patent expires-something called “patent linkage.” In some countries, regulators can’t approve a generic drug until the patent office says it doesn’t infringe. That’s not in TRIPS. But it’s in the EU-Vietnam Free Trade Agreement, the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement, and dozens of others. Data exclusivity is another TRIPS Plus trick. TRIPS doesn’t require it. But 85% of U.S. trade deals now include it. That means even if a patent expires, a generic can’t enter the market for another five to ten years. In some cases, that’s a 30-year monopoly. One drug, one company, no competition, sky-high prices. The result? In low-income countries, 65% report delays in getting generic drugs approved because of these extra rules. Meanwhile, the global generic medicine market hit $420 billion in 2020-but most of that growth happened in rich countries where people can pay. In Africa and South Asia, where the need is greatest, access barely budged.India’s Story: From Generic Superpower to Forced Compliance

India was the world’s pharmacy. In 2000, it produced 80% of the world’s HIV generics. Companies like Cipla sold combination antiretroviral pills for under $1 a day. The U.S. and EU called it piracy. India called it public health. When TRIPS forced India to switch from process to product patents in 2005, everything changed. Patents on cancer drugs like imatinib (Glivec) jumped from $2,500 to $7,000 a year. A 300% price hike. Patients died waiting. Some turned to black markets. Others just gave up. But India didn’t give up completely. It kept loopholes open. It refused to grant patents on minor modifications-like changing a pill’s color or adding a coating. That’s called “evergreening,” and TRIPS doesn’t require countries to allow it. India blocked hundreds of these fake patents. It’s one of the few countries that still fights back. Today, India still makes 60% of the world’s generic medicines. But it’s under constant pressure. The U.S. puts India on a “watch list” for intellectual property. Every year, pharmaceutical lobbyists demand tougher rules. Every year, Indian activists push back. The battle isn’t over.

What’s Changed Since COVID-19?

In October 2020, India and South Africa asked the WTO to waive TRIPS protections for COVID-19 vaccines, tests, and treatments. They argued: during a global emergency, patents shouldn’t block access. Over 100 countries supported them. The U.S., EU, and Switzerland refused. For two years, they blocked the waiver. Then, in June 2022, they gave in-but only partially. The final deal allowed countries to produce vaccines without permission, but only for low- and middle-income countries. And only for vaccines-not treatments or diagnostics. The waiver also expires in 2025. It’s not a solution. It’s a Band-Aid. Meanwhile, the Medicines Patent Pool, created in 2010, quietly negotiated licenses for 16 HIV drugs, 6 hepatitis C drugs, and 4 TB drugs. It’s reached 17.4 million people. But it’s voluntary. It only works if companies agree. And most don’t. For new drugs, especially for rare diseases, the patent system still holds the keys.Who Wins? Who Loses?

Big pharmaceutical companies say strong patents drive innovation. And they’re right-73% of new drugs since 2000 came from companies in strong IP countries. But who benefits? Not the 1.3 billion people who live on less than $2 a day. Not the millions who die from tuberculosis because they can’t afford the treatment. Not the children who can’t get malaria medicine because the price is higher than a family’s monthly income. The real winners? Shareholders. Executives. Patent lawyers. The losers? Patients. Public health systems. Developing economies trying to build their own healthcare. The numbers don’t lie. In 2000, HIV treatment cost $10,000 a year. In 2019? $75. Why? Because generics broke the monopoly. But new drugs-like those for hepatitis C or cancer-are still priced at $50,000 to $100,000. And in countries without the power to challenge patents, those prices stay.The Future of Generic Medicines

The TRIPS agreement isn’t going away. But it’s not set in stone. The 2022 waiver showed that change is possible-even if it’s slow and incomplete. The path forward? Countries need to use every legal tool they have. Compulsory licensing. Parallel imports. Patent oppositions. India’s example proves it can be done. But they need support-not threats. Global health groups are pushing for a permanent TRIPS waiver for essential medicines. Some propose a global fund to pay for R&D without patents. Others want to end data exclusivity. None of these are easy. But they’re necessary. The truth? We don’t need more patents. We need more access. More competition. More transparency. Right now, the system is designed to protect profits-not people. And until that changes, millions will keep dying because a pill costs too much.Can a country legally make generic drugs even if they’re patented?

Yes, under specific conditions. The TRIPS agreement allows compulsory licensing, where a government can authorize a local manufacturer to produce a patented drug without the company’s permission. This can happen during public health emergencies or if the drug is too expensive. But the country must first try to get a voluntary license from the patent holder, and the generics can only be used mostly within its own borders-unless it’s part of the special 2005 waiver for countries without manufacturing capacity.

Why do generic drugs cost so much less than brand-name drugs?

Generic drugs cost less because they don’t need to repeat expensive clinical trials. The original company spent years and billions developing and testing the drug. Generic makers just prove their version is biologically equivalent. They skip the R&D costs, marketing, and lobbying. That’s why a drug that costs $10,000 a year as a brand can drop to $75 as a generic. The active ingredient is the same. The price difference is about patents, not quality.

What is data exclusivity, and how does it block generics?

Data exclusivity means regulatory agencies can’t use the original drug company’s clinical trial data to approve a generic version-even after the patent expires. This creates a hidden monopoly that lasts 5 to 10 years after patent expiry. In countries with TRIPS Plus rules, this can delay generic entry by more than 15 years total. It’s not a patent. But it works like one.

Did the TRIPS waiver for COVID-19 vaccines actually help?

Not really. The 2022 WTO waiver only applied to vaccines, not treatments or tests, and only for low- and middle-income countries. It also had strict conditions and expired in 2025. No country has used it yet. The real reason vaccine access improved wasn’t the waiver-it was voluntary licenses, tech transfers, and pressure on companies to share knowledge. The waiver was symbolic, not practical.

Why doesn’t the U.S. or EU allow generic drugs to be imported from India?

They do-but only if the generics don’t violate patents. The U.S. and EU have strict patent laws and enforce them aggressively. Even if a drug is legal in India, importing it into the U.S. or EU without permission can lead to lawsuits. The system is designed to protect domestic pharmaceutical markets. That’s why Americans pay more for the same drugs sold cheaper abroad.

Jodi Harding

January 19, 2026 AT 09:02Aysha Siera

January 20, 2026 AT 17:56rachel bellet

January 22, 2026 AT 17:08Pat Dean

January 23, 2026 AT 14:49Nishant Sonuley

January 24, 2026 AT 13:36Emma #########

January 26, 2026 AT 03:38Andrew McLarren

January 26, 2026 AT 09:09Andrew Short

January 27, 2026 AT 10:02Chuck Dickson

January 27, 2026 AT 17:57Robert Cassidy

January 28, 2026 AT 08:42Naomi Keyes

January 30, 2026 AT 00:29Andrew Qu

January 30, 2026 AT 00:54Zoe Brooks

January 30, 2026 AT 02:50